Pioneers of California Mycology:

W.A. Murrill and the Fungi of the Pacific Coast

In previous columns, we’ve focused on recent discoveries in mycological science. Upcoming columns will continue in this vein, but in this column, I want to introduce a new series of articles I’m calling “Pioneers of California Mycology”, focusing on the early discoverers and contributors to our knowledge of the mycota of California. This knowledge is the result of over a century of mycological exploration by both academic mycologists and serious amateurs. All of our distinct California species and collecting spots were once unknown and undescribed and there are interesting stories to be told about their discovery. In future columns, I will cover the stories of HW Harkness, Lee Bonar, Elizabeth Morse, William Bridge Cooke, Harry Thiers, and other great figures who made invaluable contributions to California mycology over the years.

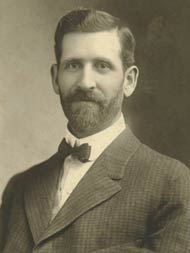

William Alphonso Murrill is one of the great names in the history of mycology, having over the course of his career, founded the journal Mycologia, published dozens of papers, originated scores of new names of fungal taxa, and traveled extensively to describe the mycota of Europe and the Americas. He was also an early “mycological evangelist”—a charismatic figure and frequent public speaker whose knowledge and enthusiasm for the study of fungi broadened the interest in mycology in a nation with little established tradition of mushroom hunting.

Murrill began his career as a curator at the New York Botanical Garden, eventually rising to the rank of Assistant Director of the Garden. Since Murrill filled mycologist Franklin Sumner Earle’s position at NYBG after the latter had left, Murrill was put in charge of mycological research at the Garden. As part of his work for the NYBG, Murrill traveled extensively to collect and describe new species of fungi. He traveled throughout the eastern United States, made several trips to Europe, as well as Mexico and the Caribbean, and to the Pacific Coast.

It was during one of these journeys that Murrill had the first of several disappearances. At some point during his 1918 trip to Europe, his usual packages of collections and correspondence ceased arriving and he failed to arrive back in Europe as scheduled. Inquiries to his colleagues at European herbaria failed to turn up any news of his whereabouts. He turned up several months later back in New York with news that he had fallen severely ill with a kidney condition and had been held up in hospital in a small French village without means of communication. Unfortunately, he also returned to find that his wife had left and sued for divorce and that the NYBG had fired him from his position as Assistant Director, demoting him to a token public outreach position at a much-reduced salary.

After 5 more years in this capacity, Murrill handed in his resignation from the Garden and soon disappeared again. This time, Murrill abandoned academic work entirely and his whereabouts were unknown to his colleagues back in New York. This would have been the end of an otherwise great academic career, but for a chance event a few years later.

In 1926, George F Weber, a mycologist and plant pathologist from University of Florida, was visiting a Gainesville resort called the Tin Can Tourist Camp along with his wife. In the recreation hall, they came across and unkempt and haggard, yet “tall, robust, dignified, pleasant stranger providing a piano concert for the transient tourists”. Weber soon recognized the stranger as none other than Murrill.

The next Summer, while convalescing from his recurring kidney problem at the University of Florida Infirmary, Murrill found that it was now the peak of the Florida mushroom season, and asked Weber for some collecting supplies, a desk, and a microscope. Weber set Murrill up with a permanent desk and research space in the only spot he could find—a landing on a stairway near the University Herbarium. Weber also arranged for a remaining $600 in publication royalties to be sent to Murill and managed to get a small stipend for him. Murrill permanently relocated to Florida, building a small house, and spending the last 34 years of his life there.

Murrill became a familiar figure around the Gainesville campus, known by many simply as “the Mushroom Man”. During the mushroom season, he would spend the morning gathering fungi in and around the campus, then return to his desk to describe and curate the collections. He would rarely return home during this time, but would work late into the evening, then fall asleep on a couch in the student union. The next morning the incoming students would rouse him and often treat him to breakfast.

During his years at Gainesville, he was also frequently visited by other eminent mycologists such as AH Smith, LR Hesler, and Rolf Singer. Singer was a frequent visitor, and the debates between Singer and Murrill on the finer points of fungal taxonomy were often made plain to anyone within shouting distance of the University Herbarium.

Murrill’s contribution to California mycology came out of his collecting trip to the Pacific Coast States in fall of 1911, while he was still at NYBG. Murrill came to the West Coast by several days train journey. He arrived first in Seattle in late October, collecting extensively at the University of Washington campus and in the city parks. He then traveled and collected in such locales as Mt Rainier, the Willamette Valley, and the Oregon Coast before moving on to California. His collecting in California was limited to the Bay Area over the period of one week in late November, but the collections he made were extensive.

On his arrival, he first set out for the UC Berkeley Herbarium where he examined many of HW Harkness’ early collections of California fungi. He next went collecting in Golden Gate Park, but as it was early in the season and still dry, came back with only a few collections, though he commented that “During a period of rainy weather, the extensive wooded areas of this park should yield a rich harvest of fungi.”

The next day, he set out for Muir Woods, which Murrill described as “the famous collecting ground in the vicinity of San Francisco”. Today a short drive from San Francisco, getting there in 1911 was a bit more involved, involving a ferry trip across the bay, a ride in an electric train up Mt. Tamalpais, and descent into Muir Woods by gravity car. There, he had better luck collecting than he had the previous day. His collections included several of the tiny colorful Lepiota characteristic of redwood forests, including two species new to science, L. castaneidisca and L. sequoiarum.

After a side trip to visit with Luther Burbank and a tour of his gardens in Santa Rosa, he next headed south to Stanford University. There, Murrill met with pioneering California botanist LeRoy Abrams and together the two set out on a collecting trip to the Santa Cruz Mountains. The first stop was in a locale known as “Preston’s Ravine” on the Old La Honda Road in Woodside, where they collected some 100 collections, including two species not described before or since, Pholiota ornatula and Melanoleuca anomala. They then drove onward to La Honda, where they even made some 50 more collections, including several more undescribed Lepiota, L. reseofolia and L. fuligenescens, as well as a couple of new species that were named for La Honda, Agaricus hondensis (one of the more common “sickner” agarics of California woodlands) and Rhodocybe hondensis. Two days were required for examination and description of the collections made from that trip, after which, he journeyed back to New York.

Over the next several years, Murrill published a series of articles in Mycologia titled "Agaricaceae of the Pacific Coast" (plus an additional article on the polypores and boletes) in which he described the fungi collected on his West Coast journey, plus additional collections sent to him by correspondents. In all, these articles described some 250 species of fleshy basidiomycetes, about half of which were newly described species (though this number partly reflects Murrill’s tendency to be a “splitter”). Murrill’s articles on Pacific Coast fungi represented an important early landmark in the description of the California mycota.

Further Reading:

- Kimbrough JW. (2003). The twilight years of William Alphonso Murrill. Mushroom, The Journal 21(3):20–24, 30–33, 46. (PDF)

- Murrill WA. (1912). Collecting fungi on the Pacific Coast. Journal of the New York Botanical Garden 13:41–44.

- Rose DW. (2003). William Alphonso Murrill: The legend of the naturalist. Mushroom, The Journal 21(1):12–15. (PDF)

- Weber GF. (1961).William Alphonso Murrill. Mycologia 53:543– 557.

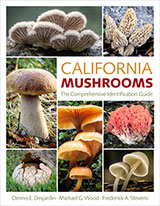

- Murrill's "Agaricaceae of the Pacific Coast" and other papers are available on MykoWeb's Murrill Literature page